How has society has changed over the last 50 years?

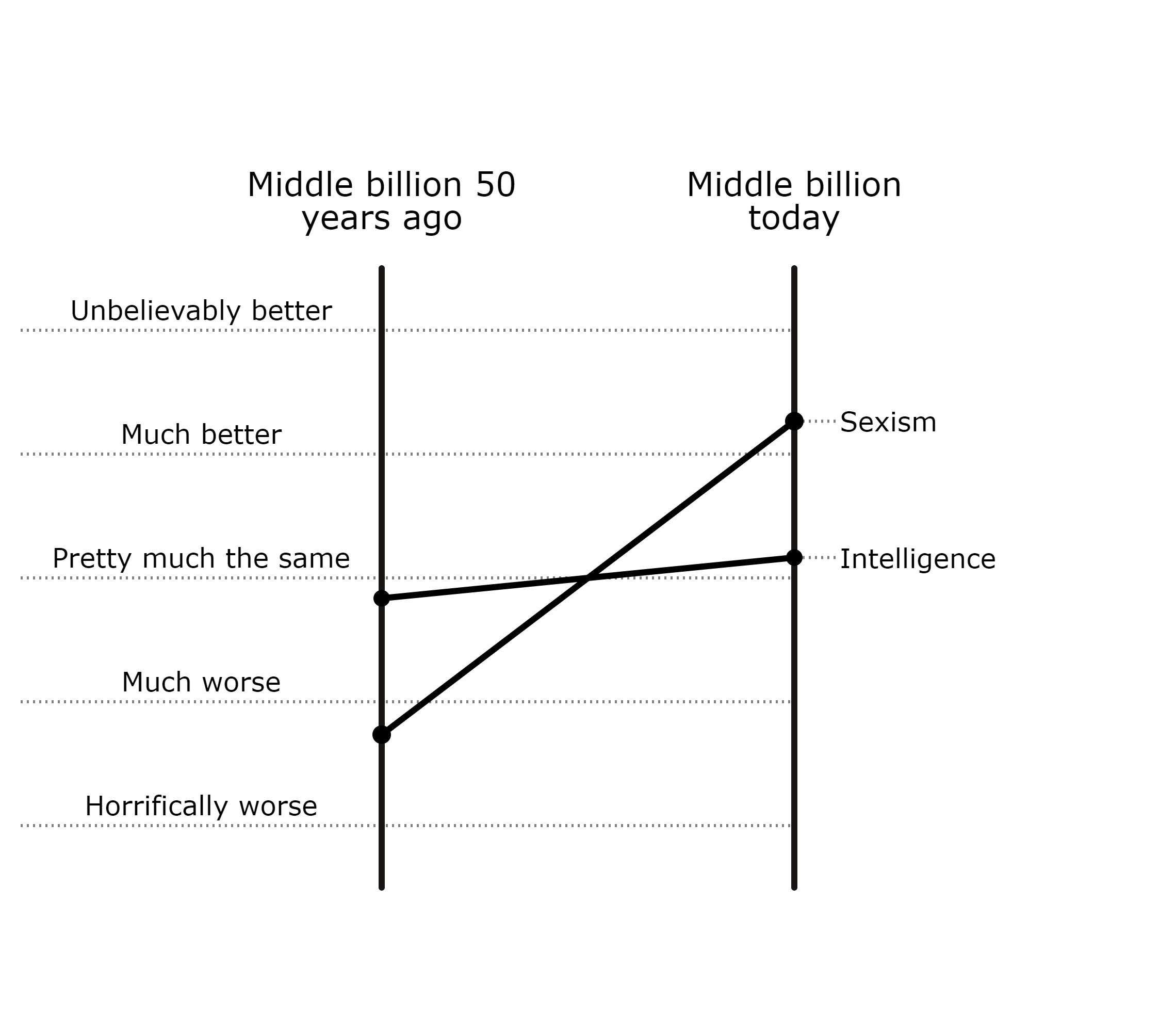

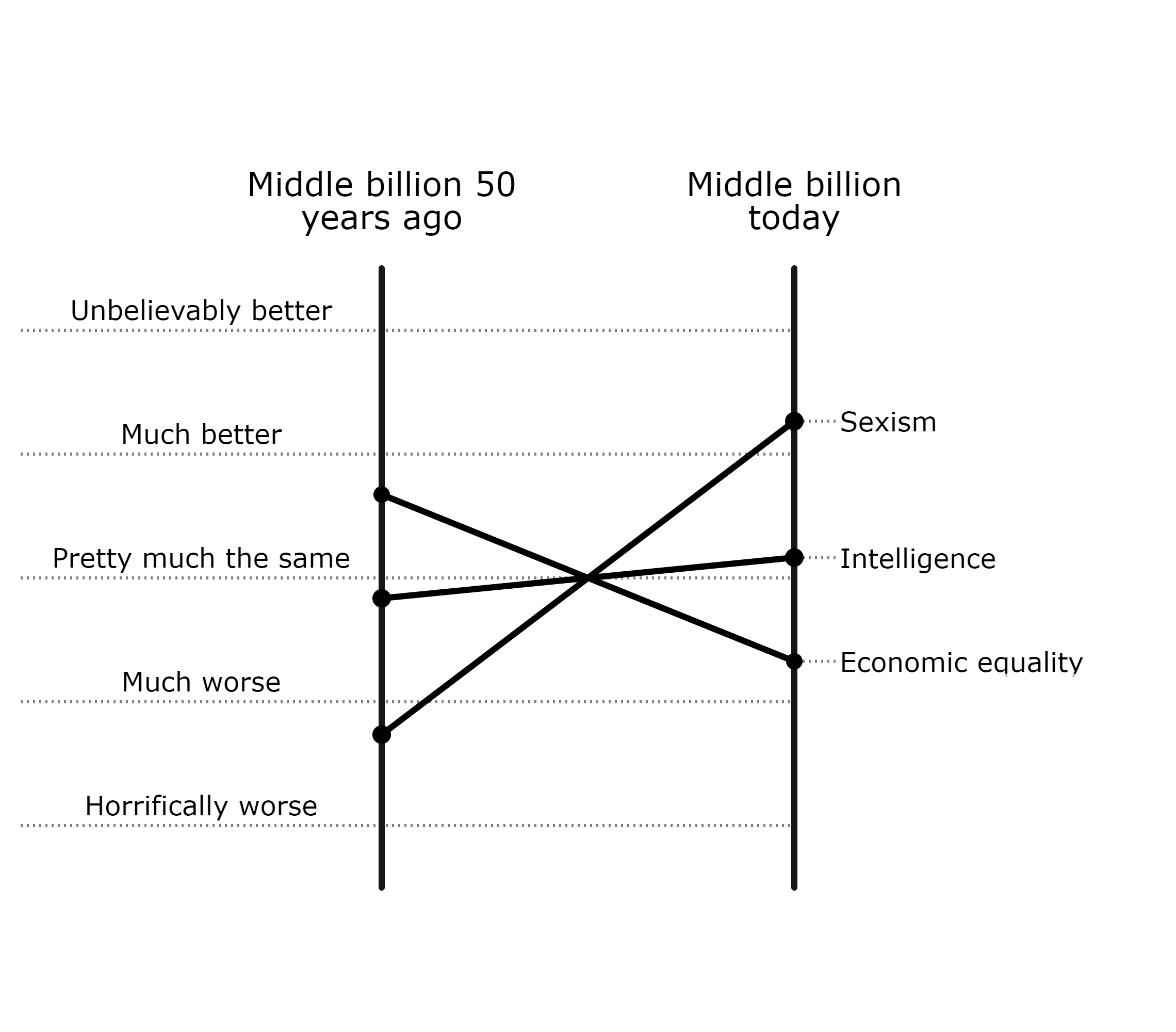

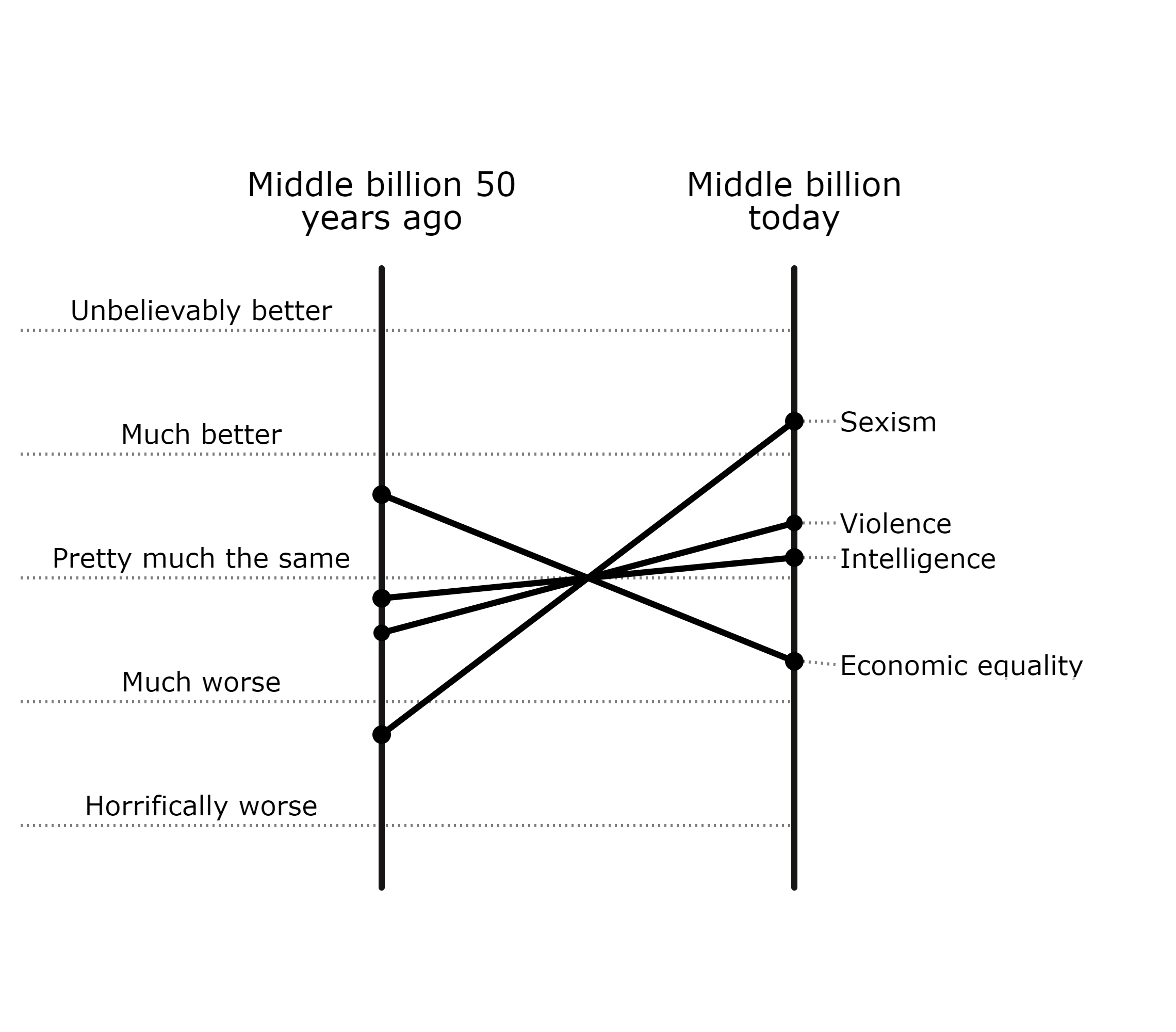

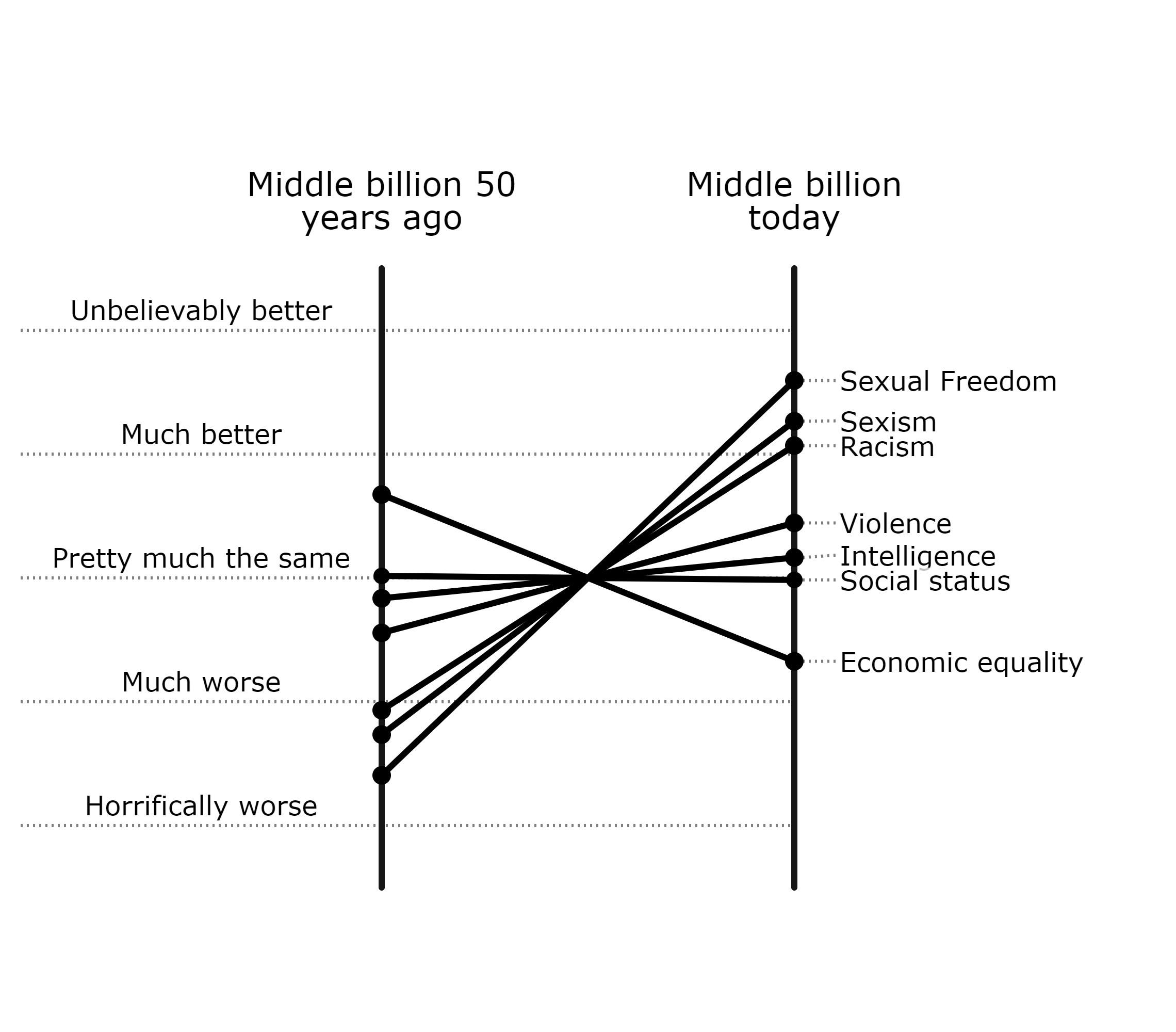

The creation of comparonomic graphs about social factors are a little more subjective for a couple of reasons. The first is that the changes are, in general, more subjective and open for debate depending on your worldview. The second is that even the direction of change and whether that is good or not is subjective.

Changes in social trends are subjective

First, we must agree how a social pattern has changed and then whether the change is in a positive direction. We can all agree that society’s acceptance of non-heterosexual behaviour has become much more prevalent. It was illegal in most places back in the 1970s. Many folks now think persecuting people based on who they love is an inappropriate thing. However, if you are at the edge of some religious groups, this acceptance of immoral behaviour is considered a horrific, scary, plummeting of moral standards. The Ku Klux Klan will not view decreased racism positively, whereas most of us think it is a great thing. For many folks, the fact that women are treated more fairly than in the past is a good thing. However, from the ISIS caliphate’s perspective, more rights for women is a bad thing and they have chosen to fix it by actions that many of us would see as making matters worse. Whether a change is good or not is a value judgment that we want to make explicit. If you are of the view that we should treat arbitrary subsections of the population as second-class citizens, then you will probably struggle with this chapter (probably the whole book, actually).

Even reduction in violence is a subjective thing. When I went to school, if a teacher got mad at you, they took you out the back and whacked you with a stick (not me, of course, given my angelic tendencies). This seems comically barbaric now but there are still those who hark back to the good old days of ‘proper’ discipline. Some states persist with the ultimate form of violence of killing citizens if they have been bad enough. Most nations have reduced violence but those who think the death penalty and hitting children is okay probably believe the trend of this reduction in violence is a bad thing. It is worth noting that even if your views on the change in the trend are different from other people, you can state that and use a comparonomic graph to illustrate it. The tool is not inherently biased but makes your view and assumptions explicit and open to debate. For each line in the comparonomic graph, we need to make three judgments:

• How has the social trend changed?

• Is the direction of change a good or bad thing?

• How much has it changed — what is the slope of the graph?

Why it matters is that rather than saying ‘morals have collapsed’ or ‘family values are much worse’, you can be explicit about how you think things have changed and whether the change is a good or a bad thing. Examples could include ‘I think there is less racism now and this is a good thing’ or ‘I think acceptance of the LGBT community has increased, and this is a bad thing.’ (not my opinion - just an example)

The list of things chosen to discuss is a small subset of everything that could be significant. Again, this list is not comprehensive or definitive but an example selection. Let us think about how the following social trends have changed over time:

• Sexism

• Intelligence

• Economic inequality

• Violence

• Sexual freedom (e.g. homophobia)

• Racism

• Social status.

Other topics that could have been included are political/religious freedom, environment, freedom of speech or acceptance of hipster beards. Some are trivial, and others could fill a whole book, e.g. trends in the environment. You can choose to explore any of these topics as well by asking:

• Which social trends are important to me?

• How have they changed over time?

• Is the change positive or negative?

In the graphs below, I assume that racism, sexism, and homophobia are undesirable and there are merits to not labelling people and persecuting them for their differences. This is not a universal opinion, but you are welcome to sketch your own version.

Social trends over the last 50 years

In each of the sections below, there is a more in-depth discussion of the social trends over the previous 50 years.

Sexism

We all know how bad sexism is around the world and the many things we need to do to improve it. Below are a few stories to put in perspective how 50 years ago it was even worse. There are mountains of statistics about why there is more equality now, like the increasing percentage of female doctors and lawyers who graduate. Instead of listing statistics, I’ll put a few examples of things that are jaw-droppingly sexist by today’s standards.

• In Switzerland, some women were not allowed to vote.

• In the US, women were not allowed to apply for a credit card without their husband’s permission.

• It was acceptable to fire women who got pregnant.

• Women were not allowed to run in marathons — presumably to protect them from too much strain.

• No woman had led an OECD country (now many have).

• The term ‘sexual harassment’ was not coined until 1975. Not because it didn’t happen but probably because it was a normal and accepted part of life.

• In the US, it was perfectly legal to rape your wife as much as you liked.

As is obvious from the Me Too movement, we have a long way to go when it comes to sexism, but we have also made a lot of progress in the last 50 years. Some countries have yet to make the full step to democracy where women are deemed fit to have a turn leading. Others have had many female leaders, so it’s barely a talking point.

The only way to interpret the trend is that there has been a significant change. Explicitly, I am going to say that the transformation has been in a positive direction while acknowledging that some people would argue that is not the case. They would likely be a minority.

Intelligence

I have included changes in intelligence to show that you can demonstrate a range of different types of changes in society on a comparonomic graph. The Flynn effect probably seems counterintuitive to most people but there is a significant body of evidence to suggest that we are consistently getting smarter by two or three IQ points per decade. IQ is not necessarily the only form of intelligence but is included here as it is easily measured and an example of other factors that can be included in comparisons.

The reasons for the IQ improvement range from better schooling, to more stimulating environments, to better nutrition and even less inbreeding (it would be impolite to mention some places where this may not be the case). It is hard to ignore the reasons for why things change but I am going to focus on the fact that there have been significant improvements in intelligence. This means that 50 years ago the average person would be around 10–15 IQ points lower. Harking back to the good old days means wishing we were significantly duller.

Economic inequality

There is growing evidence on rising inequality in the world, and in the last 50 years there has been a significant increase particularly in the OECD countries that form the middle billion. I defined our middle billion as not including the top and bottom 10% of the income population, so this has probably changed less for this group.

I am also keen to include at least something in the comparonomic graph to demonstrate that not everything has improved. There are plenty of people who would see increasing inequality as a good thing rather than a bad thing. My job here is not to judge. If you think economic inequality is good, feel free to draw your own version with the lines going the way you think they should.

It does seem that Piketty’s work along with Stiglitz and many others is increasing the perception that rising inequality is a problem. Let’s assume for argument’s sake this is a bad thing. Again, the slope of the line will inevitably be debatable.

Violence

Reading current media, we might think that violence has never been worse. Below are some examples to demonstrate the sorts of violence from 50 years ago that seem barbaric by today’s standards:

• The US thought it was acceptable to use napalm, often with civilian casualties. Cluster bombs were okay too — 270 million of them in Laos alone without acknowledging at the time they were even there.

• Soviet tanks rolled through the streets of Prague to keep the population in its place.

• A large part of current Germany was subject to the repressive Stasi police that was moving on from direct torture to perfect psychological harassment.

• The British and Irish were engaging in ‘The Troubles’ which by most measures is vastly worse than terrorism today.

• In Chile, 3000 of Pinochet’s opponents disappeared — almost certainly murdered but probably tortured as well.

• In Spain, it is thought Franco’s favoured form of torture for his political opponent was a screw through the back of the neck.

• In most countries, it was legal and accepted for government employees to hit citizens with a stick (teachers hitting students).

This list is from the histories of OECD countries. Whatever we think of our current politicians and state violence, it’s got nothing on 50 years ago. I don’t think anyone would want to go back to the more violent state of the world back then, so all we can debate is the slope of the line.

It is hard sometimes to acknowledge that things have got better when they are still unacceptably bad. Nothing about this analysis is an excuse for today’s violence. The book Factfulness made the point nicely:

‘I am saying that things can be both bad and better…I see no conflict between celebrating this progress and continuing to fight for more.’

Sexual freedom — homophobia

One encouraging trend in the last 50 years is the speed at which we have become accepting of non-heterosexual preferences. Below are a few stories to illustrate how things used to be:

• In most countries, you could be locked up — up to 20 years — for being homosexual.

• Homosexuality was listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), the bible of psychology, as a pathological illness or mental disorder.

• Words like ‘homo’, ‘faggot’ and ‘poofter’ were not that uncommon and undoubtedly not considered with the same disdain as today.

• It wasn’t that long before then that chemical or physical castration was considered an appropriate treatment for homosexuality.

• In the US, even the American Civil Liberties Union wouldn’t take on cases to challenge homosexual laws until the 1960s.

• Gay marriage was not even considered a possibility.

It seems astonishing how much attitudes have changed since then. In Ireland where 78% of people identify themselves as Catholic, they elected an openly gay prime minister. There are still plenty of folks who are horrified at the acceptance of this ‘immoral’ behaviour. I suggest that most of us now don’t give a damn about people’s sexual preferences and see the correction of this past injustice as a good thing. You can only draw a relatively steep line for this trend.

Racism

It’s clear that issues of racism are far from solved and it’s maddening we still need movements like Black Lives Matter, but let’s list a few stories from 50 years ago:

• Most countries with high immigration had openly racist immigration policies — Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the US all had strong biases for white immigrants.

• Interracial marriage wasn’t legal in all states in the US until 1967. Back then about 20% of people approved of marriage between blacks and whites, now it is 87%.

• In Australia up to the 1970s, the government was forcibly removing ‘half-caste’ children from Aboriginal mothers, so the children could be better integrated into white society. These children were known as the stolen generation. Aboriginals were not recognised as citizens until 1967 and could not own property in Queensland until 1975.

• In the early 1960s, French police massacred between 200 and 300 unarmed Algerian protesters in the heart of Paris.

• Canada still had a policy of forcibly removing indigenous children from their families and into Christian boarding schools. The goal was to help them assimilate or ‘kill the Indian in the child.’

The selection of things listed here seems outrageously racist now, and it’s by no means a comprehensive list. The fact that we have become less racist most of us believe is a good thing, and hopefully the improvements will accelerate.

Social status

Change in social status is the least debatable because we are comparing average people of one time to average people of another. Social status is the same because it is a relative thing. It also shows that some things don’t change and is a contrast to the King Louis example where he had a much higher social status. This is something explored in more detail later in the book.

Perception of happiness

There is a sense that lots of people are struggling, there is a loss of social cohesion, more depression and people seem angrier than they used to be. This particular social change is very personal and quite hard to define due to lack of adequate information from 50 years ago. Where there are long-term studies, they don’t conclusively indicate that we are significantly unhappier. However, I’m going to suggest that there is a perception of general grumpiness and at least the perception that lots of us are worse off. This perception of unhappiness is odd given many other economic and social trends seem to be in a positive direction. However, a core part of this investigation is to work out why our perceptions can be so different from reality. The entire second section of the book Comparonomics identifies the reasons we systematically feel gloomy about progress and life.

Appendix 2 also shows how you can use comparonomic graphs to represent a completely different worldview. What if you have a completely different set of social trends that are important to you? Well, you can scribble them down; when you do, it makes it easier to communicate with those who have different views on the world.

Summary of social changes over 50 years

The most significant conclusion from this short analysis is that most social trends tend to be in a positive direction. We are less racist, sexist, homophobic, and violent. Maybe society is not falling apart but getting a little more compassionate. Remember that this is not a comprehensive list of socially significant topics, but it does appear from this selection that things are getting better.

Conclusions

We have surveyed several social trends to see how they have changed and to show how comparonomic graphs can be used for non-economic questions. If we are looking out over time, there appears to be an extensive range of social changes that are trending in the direction of treating people more equally instead of judging them based on race, sex, religion, and sexual preference. If there is a trend, it seems that the rate of change is accelerating. For example, it took a long time for women to be given the vote everywhere for the OECD. It started in New Zealand in 1893, but the Swiss didn’t complete it till 1971. The change in perceptions about homosexuality seems to have changed at a much faster rate.

It is easy to forget the progress we have made given the world was almost universally homophobic, sexist, and racist as little as 100 years ago. It is good that we treat small steps backward with such outrage. The banning of people from majority Muslim countries in the US is a good example. It is excellent we are outraged but easy to forget how recently most nations had or still have race or religious based immigration policies.

The comparonomic graph is a simple way to explicitly express your view on how you think this has changed without any hidden assumptions. It is an elegant, simple way to show different values and explicitly how we think things have changed.

These tools could also be used to do a similar analysis for the environment and Appendix 2 of the book has some pointers on that. Hopefully with this perspective of how relatively well we are doing it means we are more likely to place a higher value on protecting the environment.

The critical question asked in Part One of the book Comparonomics is how well are we doing compared to people in the past? The answer is almost universally pretty damn well. The core, more baffling question is if we are doing so well, why don’t we feel like we are doing well? I suspect it is not just about convincing people they are doing well — the angst is real and needs investigating, which is what Part Two of the book covers.

Note - this is a slightly edited chapter from the book Comparonomics - the book includes links to references etc